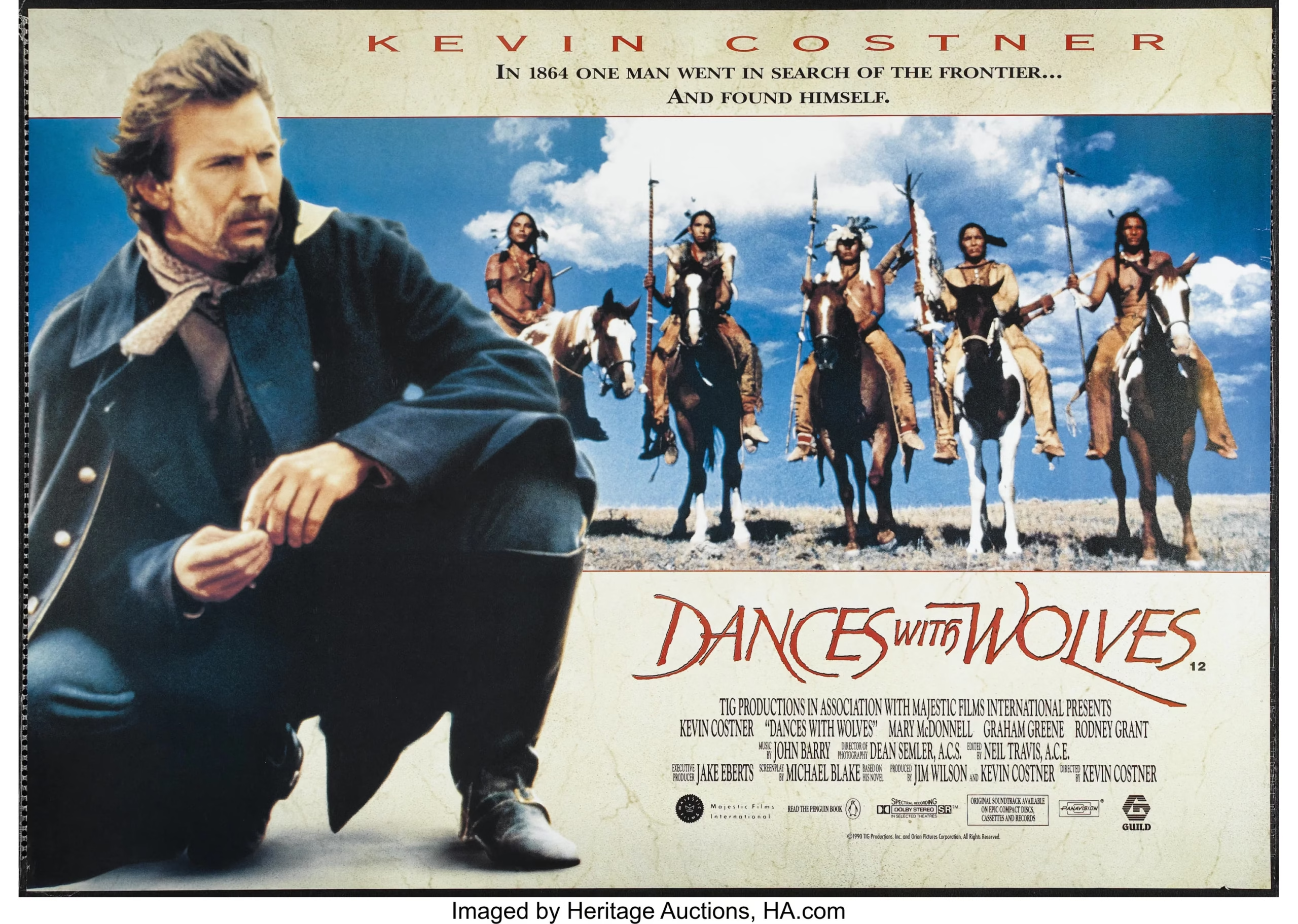

Dances with Wolves (1990) depicts the American Indian Lakota Sioux during the 1860s, a time when Native American tribes faced displacement due to U.S. expansion, broken treaties, and violence like the Sand Creek Massacre (1864). The Lakota were nomadic, relying on buffalo hunts, with a rich spiritual and communal life. However, the movie’s portrayal is idealized, often criticized for the “white savior” trope, where Dunbar becomes a central figure in the tribe’s story. Image source: Reddit

Read these first:

- History 101: The Legendary Knights of Medieval Europe

- History 101: Exploring the World’s Most Famous Old Car Museums

- History 101: Modern Toilet – Essential & The Revolutionary Transformation

- History 101: Famous Malaysian Indians & Their Major Achievements

- History 101: National Museum – Unveiling the Treasures of Our Pasts

Introduction to American Indian History

The history of American Indians is a profound narrative encapsulating the origins and evolution of numerous indigenous communities across North America. Scholars believe that the ancestors of today’s American Indians migrated from Asia, crossing the Bering Land Bridge approximately 15,000 years ago. This migration laid the groundwork for the diverse cultures and societies that would emerge throughout the continent. Over millennia, these early inhabitants adapted to different environments, leading to a variety of distinct tribes, each with unique traditions and ways of life.

As these American Indian communities developed, they established complex social structures, trade networks, and spiritual beliefs that were closely tied to the land. Tribes such as the Iroquois, Sioux, Navajo, and many others showcased remarkable cultural richness, developing intricate systems of governance, agriculture, and craftsmanship. The establishment of these diverse tribes was marked by the cultivation of various crops, fishing, and hunting practices that sustained their populations and shaped their identities.

Key historical milestones were pivotal in transforming American Indian societies. The arrival of European explorers in the late 15th century ushered in significant changes, often leading to conflicts and devastating impacts on indigenous populations through colonization, disease, and displacement. Despite these challenges, many American Indian tribes retained their unique customs, languages, and spiritual practices, reflecting a resilient heritage.

This introduction to American Indian history reveals a tapestry woven with the threads of migration, adaptation, and cultural richness. Understanding this background is essential for appreciating the complexity and depth of American Indian experiences, which continue to resonate in contemporary society. As we explore further, we will delve into how these early historical elements have influenced modern dynamics for American Indian communities today.

Please accept YouTube cookies to play this video. By accepting you will be accessing content from YouTube, a service provided by an external third party.

If you accept this notice, your choice will be saved and the page will refresh.

.

Major American Indian Tribes

The rich cultural history of American Indians is profoundly represented by several major tribes, notably the Navajo, Sioux, Cherokee, and Apache, each possessing unique customs and social structures.

The Navajo Nation, also known as Diné, is one of the largest and most prominent American Indian tribes, with a rich history rooted in the Athabaskan language family and origins tracing back to migrations from the north around 1000-1500 CE, where they developed a pastoral society centered on sheepherding, weaving, and silversmithing in the arid Southwest. Their history is marked by significant challenges, including the forced Long Walk in 1864 when thousands were marched from their lands in Arizona and New Mexico to internment in eastern New Mexico, followed by their return and the establishment of the modern Navajo Nation reservation after the Treaty of 1868.

They also played key roles in World War II as Code Talkers, using their language to create unbreakable codes. The tribe’s primary location spans parts of northeastern Arizona, northwestern New Mexico, and southeastern Utah, encompassing about 27,000 square miles—the largest reservation in the U.S.—with the capital at Window Rock, Arizona. As of recent estimates around 2025, the Navajo Nation has approximately 400,000 enrolled members, making it the largest federally recognized tribe by population.

Cherokee Nation

The Cherokee Nation, part of the Iroquoian language family, boasts a history of advanced societal structures dating to around 1000 CE, including a syllabary invented by Sequoyah in 1821 that enabled widespread literacy, a constitution modeled after the U.S. one in 1827, and a capital at New Echota; however, they endured devastating forced removal via the Trail of Tears in 1838-1839, where an estimated 4,000-15,000 perished during relocation from their ancestral Southeast homelands. This event, part of the broader Indian Removal Act, displaced them westward, leading to the formation of the modern Cherokee Nation in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma).

Today, the tribe is primarily located in northeastern Oklahoma, with additional communities in the Southeast through the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians in North Carolina and the United Keetoowah Band; their reservation and trust lands cover about 7,000 square miles. The Cherokee Nation has around 392,000 enrolled citizens as of 2025 estimates, representing the second-largest tribe and the largest among those identifying solely as Native American.

Choctaw Nation

The Choctaw Nation, from the Muskogean language family, has a history of agricultural sophistication and mound-building dating back over 2,000 years in the Mississippi River Valley, evolving into a confederacy of villages by the 16th century with a matrilineal clan system; they signed multiple treaties with the U.S. but were forcibly removed in the 1830s under the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek, enduring the Trail of Tears that halved their population due to disease and hardship.

Post-removal, they adapted by establishing a constitutional government in Indian Territory and contributing significantly during World War I as Code Talkers. The tribe’s main location is in southeastern Oklahoma, with the capital at Durant and reservation lands spanning 10,864 square miles, though many members also live in Mississippi and Louisiana via the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians. With approximately 255,000 enrolled members as of 2025, the Choctaw Nation is the third-largest tribe, known for its economic diversification, including gaming and healthcare enterprises.

Chippewa (Ojibwe/Anishinaabe)

The Chippewa, or Ojibwe/Anishinaabe, part of the Algonquian language family, trace their history to the Great Lakes region around 500 BCE, developing a birchbark canoe-based culture focused on wild rice harvesting, fishing, and maple sugaring; they formed alliances like the Council of the Three Fires with the Ottawa and Potawatomi and resisted European encroachment through the fur trade era, but faced land cessions via treaties in the 19th century and forced assimilation policies like boarding schools.

Their adaptability is evident in the 1850s Sandy Lake Tragedy, where U.S. policies led to mass deaths from starvation and disease. The tribe is located across Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, and parts of North Dakota and Ontario, Canada, with over 20 reservations, such as the White Earth and Leech Lake in Minnesota, totaling thousands of square miles. As of 2025, the Chippewa population stands at about 214,000 enrolled members across various bands, making it one of the most widespread tribes in the upper Midwest.

Sioux Nation (Lakota, Dakota, Nakota)

The Sioux Nation, encompassing the Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota divisions of the Siouan language family, has a nomadic history on the Great Plains beginning around 1700 CE after acquiring horses, excelling in buffalo hunting and warrior societies; pivotal events include the 1862 U.S.-Dakota War, the 1876 Battle of Little Bighorn where they defeated Custer, and the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre that symbolized the end of armed resistance. Treaties like Fort Laramie (1868) were repeatedly violated, leading to reservation confinement.

The Sioux are primarily located in South Dakota, North Dakota, Nebraska, Montana, and Minnesota, with major reservations like Pine Ridge (the second-largest in the U.S., over 2 million acres) and Standing Rock, where the Dakota Access Pipeline protests highlighted ongoing sovereignty struggles. The total Sioux population is estimated at around 208,000 enrolled members in 2025, divided among multiple federally recognized tribes.

Apache Tribes

The Apache, from the Athabaskan family, emerged as distinct groups around 1000-1500 CE in the Southwest, known for their guerrilla warfare tactics against Spanish, Mexican, and U.S. forces; leaders like Geronimo led resistance until his surrender in 1886, following events like the Chiricahua internment and the Bascom Affair massacre, with many surviving through adaptability in raiding and ranching. Their history reflects fierce independence amid forced relocations to Florida, Alabama, and Oklahoma.

Various Apache bands are located in Arizona, New Mexico, and Oklahoma, including the White Mountain Apache in east-central Arizona (a reservation of 1.6 million acres) and the Jicarilla in northern New Mexico. Collectively, Apache tribes number about 160,000 enrolled members as of 2025, with the White Mountain Apache alone at around 16,000, emphasizing cultural preservation through language revitalization.

Blackfeet Tribe

The Blackfeet, part of the Algonquian-speaking Blackfoot Confederacy, originated on the northern Great Plains around 1000 CE, thriving as buffalo hunters and traders with a spiritual worldview tied to the sun dance; they clashed with U.S. forces in the 19th century, notably the 1870 Marias Massacre where 200 were killed, and signed the 1855 Lame Bull Treaty that ceded vast lands, leading to reservation life amid starvation from declining buffalo herds.

The tribe maintains strong ties to the Northern Piikani in Canada. Their location centers on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation in northwestern Montana, bordering Glacier National Park and spanning 1.5 million acres. As of 2025, the Blackfeet Tribe has approximately 17,000 enrolled members, though broader identification reaches 159,000, focusing on economic development through tourism and energy resources.

Muscogee (Creek) Nation

The Muscogee (Creek) Nation, Muskogean speakers, formed a complex chiefdom of towns and mound centers in the Southeast by 1000 CE, blending Mississippian culture with trade networks; they allied variably in colonial wars but faced removal via the 1830s Trail of Tears under the Treaty of Cusseta, losing their Georgia heartland and enduring high mortality during relocation to Indian Territory.

The 1979 reunification of factions strengthened their governance. Located primarily in east-central Oklahoma, the nation controls about 75,000 acres of trust land with the capital at Okmulgee. The Muscogee Nation has around 108,000 enrolled citizens as of 2025, renowned for cultural festivals like the Creek Indian Memorial Day and successful enterprises in gaming and media.

Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) Confederacy

The Haudenosaunee, or Iroquois Confederacy (Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and later Tuscarora), formed around 1142-1450 CE in the Northeast as a democratic alliance of the Great Law of Peace, influencing the U.S. Constitution; they navigated European alliances in the Beaver Wars but suffered land losses post-Revolutionary War via treaties like Fort Stanwix (1784), with internal divisions during the American Revolution.

The confederacy persists as a sovereign entity. Spanning upstate New York, with reservations like the Seneca Nation’s 99,000 acres, and extensions into Canada and Oklahoma. The six nations collectively have about 115,000 enrolled members in 2025, advocating for treaty rights and environmental justice, such as in the Standing Rock solidarity.

Seminole Tribe of Florida

The Seminole, emerging in the 18th century from Creek migrants and other Southeastern groups in Florida, resisted U.S. expansion through three Seminole Wars (1816-1858), led by figures like Osceola, resulting in forced removals but with many evading capture in the Everglades; survivors formed the core of the modern tribe, gaining federal recognition in 1957 after economic adaptation via cattle ranching.

Their history underscores resilience against removal policies. Located in southern Florida, primarily on the 86,000-acre Brighton and Big Cypress reservations, with urban communities in Miami. The Seminole Tribe of Florida has approximately 4,300 enrolled members as of 2025, part of a broader Seminole population exceeding 20,000, including Oklahoma branches, bolstered by gaming revenues from Hard Rock International.

Please accept YouTube cookies to play this video. By accepting you will be accessing content from YouTube, a service provided by an external third party.

If you accept this notice, your choice will be saved and the page will refresh.

.

Tribal Sovereignty and Legal Protection

Tribal sovereignty is a fundamental concept that recognizes American Indian tribes as distinct nations with the authority to govern themselves. This status is rooted in historical agreements made between the American Indian tribes and the U.S. government, commonly referred to as treaties. These treaties, which date back to the early interactions between American Indian and European settlers, established not only the rights of American Indian tribes but also defined their territories and responsibilities. Over time, the importance of American Indian tribal sovereignty has been acknowledged within U.S. law, granting American Indian tribes certain legal rights and protections.

Under federal law, American Indian tribes possess the right to self-governance, which allows them to establish their own laws and regulations, manage their lands, and conduct affairs independently from state jurisdiction. The foundation for this legal status is found in landmark legislation such as the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975. This act empowers American Indian tribes to control programs and services that impact their communities, fostering a sense of autonomy and self-sufficiency.

Moreover, tribal sovereignty extends to various areas, including healthcare, education, and law enforcement. The legal rights afforded to American Indian tribes often intersect with issues of land rights, resource management, and cultural preservation. Courts have generally upheld the principle that tribes have the authority to regulate intra-tribal matters without external interference, thus reinforcing the concept of legal protection for American Indian tribal sovereignty. However, challenges remain, particularly in navigating the complexities of state and federal laws that can sometimes conflict with tribal regulations.

Ultimately, recognizing and respecting tribal sovereignty is crucial for the continued existence and vitality of American Indian tribes in the modern landscape. The path forward involves ongoing dialogue, legal advocacy, and legislative support to ensure that the rights of these distinct American Indian nations are acknowledged and preserved. This commitment to legal protection plays a vital role in safeguarding the cultural heritage and sovereignty that is intrinsic to the identity of American Indian tribes.

Impact of European Colonization

The arrival of European settlers in the Americas marked a significant turning point for American Indian populations. As colonization progressed, Indigenous communities faced profound and often devastating changes. One of the most immediate consequences was land dispossession. European settlers claimed large areas of land for agriculture and settlement, frequently disregarding the rights of the American Indian inhabitants. Treaties were made and repeatedly broken, leading to erosion of Indigenous territories and ultimately, their traditional way of life. This displacement triggered numerous conflicts, such as the Pequot War and King Philip’s War, which resulted in considerable loss of life and further increased tensions between American Indians and settlers.

Alongside land dispossession, the colonization period was marked by aggressive cultural assimilation efforts. European powers sought to impose their cultural norms and religious beliefs on Indigenous populations, often through missionization and education initiatives. These efforts aimed not only to convert American Indians to Christianity but also to erase their languages, customs, and spiritual practices. Schools were established to indoctrinate Indigenous children, promoting Eurocentric values while deemphasizing their heritage, which led to long-term impacts on cultural continuity.

Another factor that dramatically altered the dynamics of Native American societies was the introduction of foreign diseases by European colonizers. Illnesses such as smallpox, measles, and influenza ravaged Indigenous communities, who had no immunity to these new pathogens. The demographic cataclysm caused by these diseases decimated populations, leading to the collapse of entire tribes and leaving survivors ill-equipped to resist encroaching settlers. This convergence of land loss, cultural suppression, and health crises illustrates the multidimensional impacts of European colonization on Native American communities, setting the stage for the complex interactions between these groups and the settlers in subsequent centuries.

Please accept YouTube cookies to play this video. By accepting you will be accessing content from YouTube, a service provided by an external third party.

If you accept this notice, your choice will be saved and the page will refresh.

.

Famous American Indians

Sacagawea (Shoshone)

Sacagawea, born around 1788 in present-day Idaho, was a Shoshone woman who became an essential guide and interpreter for the Lewis and Clark Expedition from 1804 to 1806. Kidnapped as a teenager by the Hidatsa and married to French-Canadian trapper Toussaint Charbonneau, she joined the expedition at age 16 while pregnant, giving birth to her son Jean Baptiste en route.

Her knowledge of the western landscape, ability to identify edible plants, and diplomatic skills in negotiating with Shoshone tribes for horses and supplies were instrumental in the Corps of Discovery’s success in reaching the Pacific Ocean. Often romanticized in American folklore, Sacagawea’s legacy symbolizes resilience and cultural bridging, though historical records debate details of her later life; she died around 1812 or 1884, with her story immortalized on the U.S. dollar coin.

Sitting Bull (Hunkpapa Lakota)

Sitting Bull, born around 1831 in present-day South Dakota, was a revered Hunkpapa Lakota leader and holy man who united Sioux tribes against U.S. encroachment on their Great Plains homelands. A visionary who interpreted dreams as omens, he played a pivotal role in the 1876 Great Sioux War, leading warriors to victory at the Battle of the Little Bighorn, where General George Custer’s forces were decisively defeated.

Refusing to sign the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, which ceded lands, Sitting Bull evaded capture for years before surrendering in 1881; he later joined Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show but returned to activism. Arrested in 1890 amid the Ghost Dance movement, he was killed by tribal police during an altercation, becoming a martyr for Native sovereignty. His resistance highlighted the Lakota’s fight for cultural preservation amid forced assimilation.

Crazy Horse (Oglala Lakota)

Crazy Horse, born around 1840 in present-day South Dakota, was an Oglala Lakota warrior and tactician renowned for his unyielding defense of Sioux lands during the Great Sioux War of 1876-1877. Known for his spiritual visions and humble demeanor—refusing to allow his photograph—he led daring raids against U.S. troops and was a key commander at the Battle of Little Bighorn alongside Sitting Bull.

After the U.S. victory at the Battle of Wolf Mountain, Crazy Horse surrendered in 1877 to secure food for his starving people but was betrayed and fatally bayoneted while allegedly resisting arrest at Fort Robinson, Nebraska. His legacy endures as a symbol of Lakota bravery and independence, with the Crazy Horse Memorial in the Black Hills honoring his fight against colonization.

Geronimo (Bedonkohe Apache)

Geronimo, born in 1829 in what is now Arizona, was a Bedonkohe Apache leader whose name became synonymous with fierce resistance to Mexican and U.S. expansion in the Southwest. After Mexican soldiers massacred his family in 1858, he joined raids across the border, earning notoriety for evading capture through guerrilla tactics.

Leading Chiricahua Apache bands, he surrendered multiple times under broken treaties before escaping the San Carlos Reservation in 1881 and 1885, prolonging the Apache Wars until his final surrender in 1886, which required one-quarter of the U.S. Army. Imprisoned in Florida, Alabama, and Oklahoma, he converted to Christianity, dictated his autobiography, and died in 1909 as a prisoner of war. Geronimo’s story embodies Apache defiance and the human cost of U.S. imperialism.

Tecumseh (Shawnee)

Tecumseh, born around 1768 in present-day Ohio, was a Shawnee diplomat and visionary who sought to forge a pan-Indian confederacy to halt American westward expansion after the Revolutionary War. Influenced by his brother Tenskwatawa’s prophecies, he traveled across tribes from the Great Lakes to the Gulf, advocating unity against land cessions and forming Prophetstown as a cultural revival center.

His efforts culminated in alliances during the War of 1812, siding with the British, but he was killed at the Battle of the Thames in 1813. Tecumseh’s eloquent speeches and strategic alliances challenged U.S. manifest destiny, inspiring future Native activism and leaving a legacy of intertribal solidarity against colonialism.

Sequoyah (Cherokee)

Sequoyah, born around 1770 in present-day Tennessee, was a Cherokee silversmith and self-taught inventor who created the Cherokee syllabary in 1821, transforming the tribe into one of the most literate Indigenous nations. Illiterate himself and injured in battle, he spent over a decade developing a writing system of 86 characters representing syllable sounds, enabling rapid literacy and the publication of the Cherokee Phoenix newspaper in 1828.

Despite opposition from traditionalists who feared witchcraft, his invention facilitated a constitution, schools, and legal defenses against removal. Sequoyah later aided Cherokee reunification post-Trail of Tears and died around 1843 in Mexico seeking lost kin. His syllabary remains in use, symbolizing Native intellectual achievement amid cultural erasure.

Chief Joseph (Nez Perce)

Chief Joseph, born Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt in 1840 in present-day Oregon, was a Nez Perce diplomat who led his band in a desperate 1,170-mile flight to Canada in 1877 to evade forced relocation from their Wallowa Valley homeland.

Facing broken treaties, he navigated through U.S. troops, delivering the poignant surrender speech, “I will fight no more forever,” after losing over 200 people, including women and children. Exiled to Oklahoma and later Washington, he advocated for his people’s return until he died in 1904, possibly from poisoning. Joseph’s eloquence and humane leadership during the Nez Perce War exemplify peaceful resistance and the tragedy of U.S. expansionism.

Pocahontas (Powhatan)

Pocahontas, born around 1596 in present-day Virginia, was a Powhatan princess whose interactions with English settlers at Jamestown shaped early colonial relations. Daughter of Chief Wahunsenacawh, she befriended Captain John Smith in 1607—legend says saving his life from execution, though likely a ritual—and facilitated food supplies during the “Starving Time.”

Baptized Rebecca and married John Rolfe in 1614, her union brought a temporary peace, but she died in 1617 at age 21 in England from illness or smallpox. Romanticized in folklore, Pocahontas’s real story highlights Powhatan diplomacy and the exploitative dynamics of colonization.

Jim Thorpe (Sac and Fox)

Jim Thorpe, born Wa-Tho-Huk in 1887 in Oklahoma Territory, was a Sac and Fox athlete dubbed “the greatest athlete in the world” after winning gold medals in the pentathlon and decathlon at the 1912 Stockholm Olympics.

Excelling in football, baseball, and basketball despite boarding school assimilation, he played professionally but lost his medals in 1913 over amateurism violations (restored in 1983). An advocate for Native rights, Thorpe founded the American Indian Athletic Hall of Fame and starred in early films. Struggling with poverty, he died in 1953, but his legacy as a multi-sport icon inspires Indigenous youth to overcome systemic barriers.

Wilma Mankiller (Cherokee)

Wilma Mankiller, born in 1945 in Oklahoma, was the first female principal chief of the Cherokee Nation from 1985 to 1995, leading economic revitalization and community health programs that increased enrollment by 20%. Relocating to California during termination policies, she returned to advocate for self-determination, founding programs for rural development and women’s leadership.

Despite health challenges, including kidney transplants, her tenure emphasized cultural preservation and sovereignty, earning the Medal of Freedom in 1998. Mankiller, who died in 2010, remains a trailblazer for Native women in governance and activism.

Please accept YouTube cookies to play this video. By accepting you will be accessing content from YouTube, a service provided by an external third party.

If you accept this notice, your choice will be saved and the page will refresh.

.

Cultural Preservation and Revival

The preservation and revival of American Indian cultures have become a vital concern among indigenous communities and cultural advocates. With the impact of colonization and modernization, many traditions, languages, and customs faced significant threats. However, numerous initiatives have emerged over the years to counteract these challenges, aimed explicitly at maintaining and revitalizing the rich cultural heritage of American Indians.

Cultural education plays a pivotal role in these revival efforts. Schools and tribal organizations have developed programs that emphasize the importance of indigenous languages, customs, and historical narratives. Through curricula that incorporate traditional teachings, American Indians strive to educate younger generations about their heritage, ensuring they retain a connection to their roots. Language revitalization projects, such as the creation of language immersion schools, have gained momentum, helping to foster fluency and pride in native languages.

Storytelling remains an essential aspect of cultural preservation. Elders within the community often take on the role of storytellers, passing down ancestral knowledge and life lessons through oral traditions. These narratives cultivate a sense of identity and belonging and serve as a means of connecting generations. The practice of sharing stories, whether through community gatherings or formal events, helps preserve the language and traditions while fostering resilience and solidarity within communities.

Furthermore, the arts have become a vital tool for cultural expression. Indigenous artists utilize various media, from painting to sculpting, demonstrating their cultural narratives and artistic innovations. Ceremonial practices, which encompass traditional dances, music, and rituals, also play a crucial part in cultural revival. These ceremonies not only provide a platform for expressing cultural identity but also reinforce community bonds. The commitment to the arts and rituals fosters pride in indigenous heritage, ensuring that the rich tapestry of American Indian cultures continues to thrive in modern society.

Final Say

The journey of American Indians is marked by a rich historical tapestry, characterized by resilience and adaptability in the face of numerous challenges. As we reflect on their past, it becomes evident that understanding their history is crucial not only for appreciating their contributions but also for acknowledging the ongoing struggles they face in modern society. This understanding fosters empathy and encourages broader support for issues affecting Native peoples today.

In today’s rapidly changing world, American Indian tribes are navigating a landscape filled with both challenges and opportunities. Modern realities present complexities, including economic disparities, legal battles for sovereignty, and the preservation of cultural identities. Despite these hurdles, many tribes are harnessing their heritage to drive economic development, leveraging tourism, renewable energy projects, and cultural arts to enhance community well-being and education.

Advocacy for American Indians is vital, as continued support from citizens and policymakers alike can lead to effective frameworks that empower these communities. Recognizing the historical injustices faced by Native peoples will pave the way for actions that promote equity and justice. By raising awareness of American Indian contributions—be it through art, governance principles, or ecological stewardship—we enrich the broader American narrative.

The future of American Indians holds promise, driven by renewed efforts for self-determination and recognition of their rights. As tribes increasingly engage with local, national, and global platforms, it is essential to support initiatives that honor their heritage while fostering modern advancements. The journey of American Indians is not only a testament to their strength but also a reminder of the collective responsibility to ensure their voices are heard and valued in all realms of society.