A primary goal in national water resource management strategies is to augment water reserves, ensuring a sustainable supply for various needs. Concurrently, it’s crucial to minimize non-revenue water—water that is produced but not billed due to factors like leaks, theft, or metering inaccuracies. By addressing these challenges, countries can promote water conservation, improve service delivery, and enhance the financial viability of water utilities. Image source: Facebook

Read these first:-

- Environment 101: Clueless Kelantan PAS & Humourless Water Resource Management

- Prepping 101: Doomsday Bunker – Part 3: Clean, Good Water & Food Supply

- Water Pollution 2021: Two Water Disruptions, Faster Recovery This Time

- Water Pollution 2020: Why We Are Not Punishing Everyone For Water Disruptions?

- National Security 2020: Part 2 – Treat Water Pollution as Terrorist Attack!!

Water Reserve Margin and Non-Revenue Water

Water reserve margin and non-revenue water (NRW) are critical concepts in the sphere of water resource management. Understanding these terms is pivotal for ensuring sustainable and efficient water supply systems. The water reserve margin refers to the surplus capacity available in a water supply system above the current demand. This margin acts as a buffer to cope with unexpected increases in demand or potential failures in the system. It is calculated by comparing the total water supply capacity with the actual consumption levels. A healthy water reserve margin is vital for maintaining a reliable water supply, especially during peak demand periods or emergencies.

Non-revenue water, on the other hand, encompasses the water that is produced but not billed to consumers. This can result from various factors such as leaks in the distribution system, unauthorized consumption, and inaccuracies in metering. NRW represents a significant challenge for water utilities as it directly impacts their financial sustainability and operational efficiency.

Leaks in pipes and distribution networks primarily contribute to NRW, leading to substantial water losses. Theft or unauthorized water usage further exacerbates the issue, causing financial losses and resource misallocation. Additionally, metering inaccuracies, whether due to faulty meters or administrative errors, can inflate NRW figures, complicating efforts to measure and manage water resources accurately.

The implications of non-revenue water are far-reaching. High levels of NRW not only result in financial losses for water utilities but also strain the available water resources, leading to inefficiencies in water distribution and supply.

Addressing NRW involves a multifaceted approach that includes regular maintenance of infrastructure, implementation of advanced metering technologies, and stringent measures to prevent unauthorized water usage. By effectively managing water reserve margins and reducing NRW, water utilities can enhance their service delivery, ensure sustainable water supply, and improve overall water resource management.

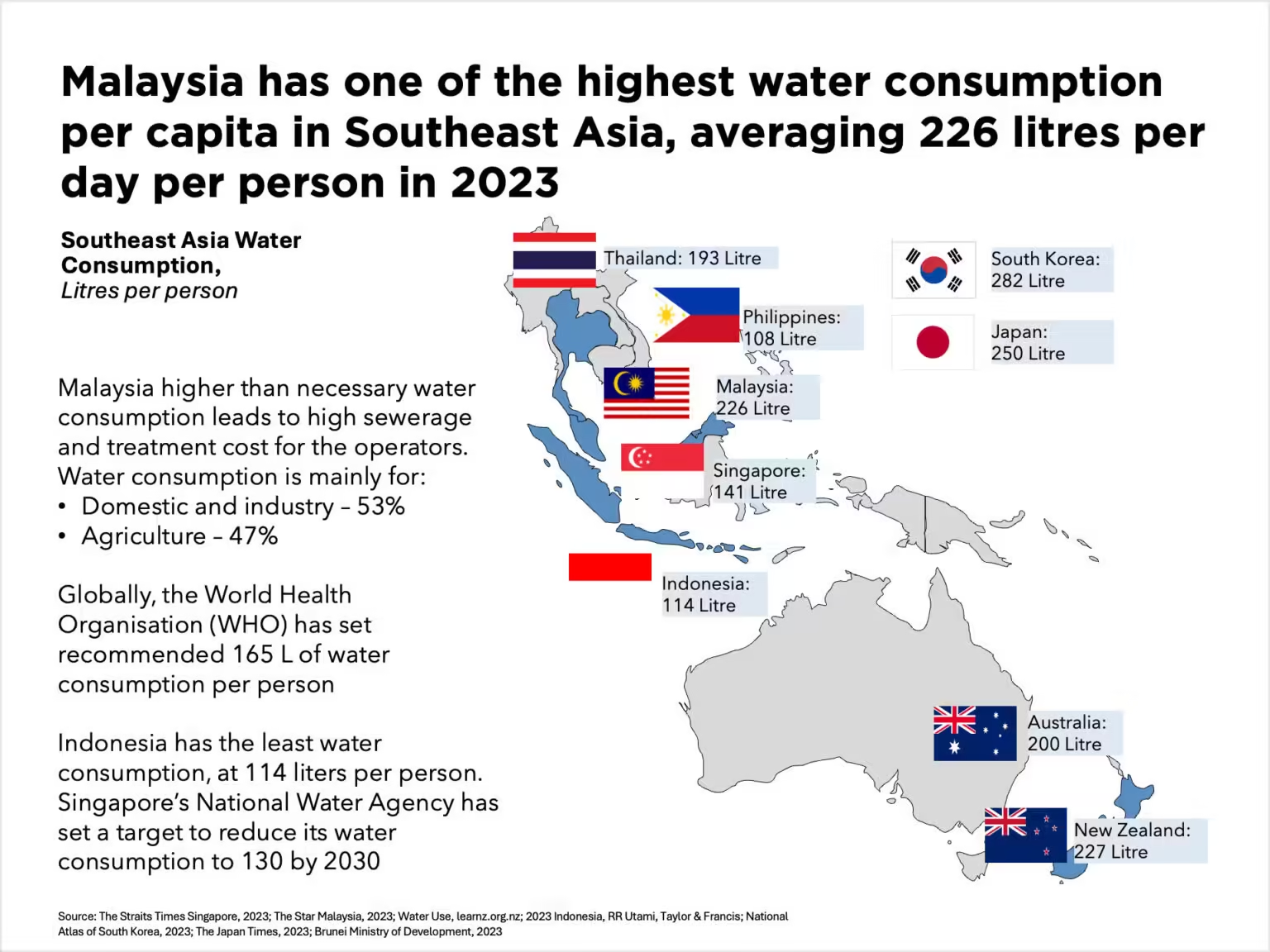

In Malaysia, the water consumption rates are notably high, with an average domestic usage of 245 liters per capita per day, which exceeds the United Nations’ daily water requirement benchmark of 165 liters per person. Despite this high usage, Malaysians benefit from a relatively low, subsidized water tariff, which was recently adjusted to RM1.22 (approximately USD0.29) per cubic meter. In contrast, New Zealand’s average water consumption stands at 227 liters per person per day, with a higher water tariff rate of NZD 2.36 (around USD1.50) per cubic meter as of the 2024/25 rating year. These figures highlight the significant differences in water usage and cost between the two nations. Image source: Pemandu

International Standards for Water Reserve Margin

Globally, maintaining an adequate water reserve margin is crucial for ensuring a sustainable and reliable water supply. Several international bodies, including the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Water Association (IWA), have established guidelines and benchmarks to assist countries in managing their water resources effectively.

The WHO emphasizes the necessity of a water reserve margin to safeguard public health. According to WHO guidelines, a reserve margin of 10-15% above the average daily demand is recommended. This buffer is essential for addressing unexpected surges in water demand, climatic variability, and potential system failures. WHO’s standards aim to mitigate the risks associated with water scarcity, ensuring that communities have continuous access to safe drinking water.

Similarly, the IWA provides comprehensive guidelines on water reserve margins, focusing on the technical and operational aspects of water supply systems. The IWA advocates for a more dynamic approach, suggesting that the reserve margin should be adaptable based on factors such as population growth, urbanization, and environmental changes. By doing so, the IWA aims to promote resilience in water supply systems, enhancing their ability to cope with both short-term disruptions and long-term stresses.

The rationale behind these international standards is to create a framework that supports sustainable water management. Adequate reserve margins help prevent over-extraction of water resources, thereby protecting ecosystems and maintaining the natural water balance. Additionally, they provide a buffer against the uncertainties of climate change, which can lead to unpredictable fluctuations in water availability.

Ultimately, adherence to these internationally recognized standards helps ensure service reliability. By maintaining recommended water reserve margins, water utilities can better manage supply and demand, reduce the risk of service interruptions, and improve overall water security. These standards serve as a critical tool for policymakers and water managers worldwide, guiding them towards practices that uphold the principles of sustainability and reliability in water supply systems.

International Standards for Non-Revenue Water

Non-revenue water (NRW) represents a significant challenge for water utilities worldwide. It refers to water that has been produced and is “lost” before it reaches the customer. The International Water Association (IWA) has set comprehensive standards and guidelines aimed at managing and reducing NRW to improve water efficiency and sustainability globally.

Among the various international standards, the IWA’s Water Loss Task Force has established key performance indicators (KPIs) and best practices. One of the primary targets set by IWA includes reducing NRW to less than 15% of the total water supply. Achieving this target requires a multifaceted approach encompassing several methodologies.

Active leak detection is a cornerstone methodology recommended by IWA. It involves using acoustic devices, correlators, and advanced technologies to identify and repair leaks promptly. This proactive approach helps mitigate water loss and maintain system integrity. Additionally, pressure management is another critical practice. By optimizing water pressure within the distribution network, utilities can significantly reduce the incidence of leaks and bursts, thereby curbing NRW.

Customer metering improvements also play a crucial role in reducing non-revenue water. Accurate metering ensures that water usage is precisely measured and billed, minimizing discrepancies and unauthorized consumption. By upgrading to smart meters and implementing automated meter reading (AMR) systems, utilities can enhance data accuracy and facilitate real-time monitoring of water consumption patterns.

Furthermore, the IWA emphasizes the importance of regular audits and performance assessments. Water utilities are encouraged to conduct periodic water audits to identify inefficiencies and implement targeted interventions. These audits provide valuable insights into the sources of NRW and help prioritize actions for improvement.

Globally, several water utilities have successfully implemented these standards and methodologies. For instance, utilities in Singapore and Denmark have achieved remarkable reductions in NRW through rigorous leak detection programs, comprehensive pressure management, and extensive customer engagement. These examples underscore the effectiveness of adhering to international standards in managing non-revenue water.

Water Reserve Margin in Malaysia: National Overview

The water reserve margin in Malaysia represents a critical component of the nation’s water management strategy. This margin, defined as the surplus capacity of water supply over demand, is essential for ensuring a reliable and uninterrupted water supply, especially during peak usage periods or unforeseen disruptions. National statistics indicate that Malaysia’s water reserve margin varies significantly across its different states, reflecting diverse regional demands and supply capabilities.

According to recent data, several states in Malaysia, such as Selangor, Kedah, and Penang, have experienced fluctuating water reserve margins over the past decade. For instance, Selangor, a state with a high population density and significant industrial activities, has frequently reported margins below the recommended international standards, which typically advocate for a reserve margin of 15-20%. In comparison, states with lower population densities usually maintain healthier reserve margins, aligning more closely with global benchmarks.

Maintaining an adequate water reserve margin presents numerous challenges. These include rapid urbanization and industrialization leading to increased water demand, aging infrastructure causing inefficiencies, and climatic variations impacting water availability. Furthermore, non-revenue water (NRW), which encompasses water loss due to leaks, theft, or metering inaccuracies, exacerbates the difficulty in sustaining suitable reserve margins. Malaysia’s NRW levels are relatively high, averaging around 35%, which significantly strains the water supply system.

Despite these challenges, Malaysia has made notable strides in improving its water reserve margins. Recent government initiatives include substantial investments in upgrading water infrastructure, adopting advanced water management technologies, and implementing stricter regulatory measures. The National Water Services Commission (SPAN) has also been proactive in setting higher standards for water treatment and distribution, fostering more efficient water usage practices.

In conclusion, while Malaysia faces significant hurdles in maintaining adequate water reserve margins, ongoing efforts and policies demonstrate a commitment to securing a sustainable and reliable water supply for its population. Continued focus on infrastructure improvement, technological adoption, and effective water management practices will be crucial in aligning Malaysia’s water reserve margins with international standards.

In 2023, Malaysia faced a significant challenge with non-revenue water (NRW), which refers to treated water that is lost before it reaches consumers, often due to leaking pipes or non-functioning meters. The national level of NRW was reported at 37.2%, with certain states like Kelantan experiencing a higher rate of 53.7%. The reasons for this high level of NRW are multifaceted, including aging infrastructure, inadequate maintenance, and the need for substantial capital investment to upgrade the water distribution systems. Image source: Hawle

Non-Revenue Water in Malaysia: National Overview

Non-revenue water (NRW) represents a significant challenge for water management systems worldwide, and Malaysia is no exception. As of recent data, Malaysia’s NRW stands at approximately 35%, which is notably higher than the international benchmark of 15%. This disparity underscores the urgency for Malaysia to address the inefficiencies within its water supply network.

The primary causes of NRW in Malaysia are multifaceted, comprising physical losses due to leaks and bursts, commercial losses from unauthorized consumption, and metering inaccuracies. Physical losses alone account for the majority of NRW, driven by aging infrastructure and inadequate maintenance. Commercial losses, including illegal connections and theft, further exacerbate the issue. Additionally, outdated and inaccurate metering systems hinder precise water usage tracking, contributing to the overall NRW percentage.

The economic and environmental impacts of high NRW levels are profound. Economically, it translates to substantial financial losses for water utilities, which are unable to recover costs for the water that is produced but not billed. This inefficiency can lead to increased tariffs for consumers to offset the losses. Environmentally, high NRW results in unnecessary water extraction, stressing natural water sources and ecosystems. The excessive energy consumption required to treat and pump water that is ultimately lost also contributes to a larger carbon footprint.

In response to these challenges, the Malaysian government, alongside water utilities, has implemented several strategies to mitigate NRW. These include infrastructure upgrades, such as replacing old pipes and enhancing leak detection mechanisms. Advanced meter infrastructure (AMI) is being adopted to improve accuracy in water usage measurement and billing. Additionally, public awareness campaigns are being conducted to educate consumers on the importance of water conservation and the impacts of NRW.

Collaboration with international experts and the adoption of best practices from countries with lower NRW rates are also part of Malaysia’s comprehensive approach. By integrating advanced technologies and fostering a culture of sustainability, Malaysia aims to significantly reduce its NRW levels, thereby enhancing the efficiency and reliability of its water supply system.

Water Reserve Margin and NRW by State in Malaysia

In Malaysia, the water reserve margin and non-revenue water (NRW) statistics vary significantly across different states. The water reserve margin, which indicates the buffer capacity of the water supply system, is a critical measure of water security. Non-revenue water, on the other hand, refers to water produced but not billed to customers, often due to leaks, theft, or inaccurate metering.

States such as Selangor and Penang are frequently highlighted for their exemplary performance in managing water resources. Selangor boasts a relatively high water reserve margin, attributed to its advanced infrastructure and efficient water management practices. Penang, renowned for its low NRW percentage, has implemented stringent measures to minimize water losses, including regular maintenance and the use of modern technologies.

Conversely, states like Kelantan and Sabah face significant challenges in maintaining adequate water reserve margins and reducing NRW levels. Kelantan has struggled with aging infrastructure and limited investment in water management systems, resulting in a lower water reserve margin. Similarly, Sabah’s vast and rugged terrain complicates the maintenance and monitoring of its water supply network, leading to higher NRW percentages.

Several factors contribute to these disparities across Malaysian states. Infrastructure quality is a primary determinant, with states investing in modern, resilient systems enjoying better water reserve margins and lower NRW rates. Population density also plays a critical role; densely populated areas like Kuala Lumpur and Selangor benefit from economies of scale in water supply and management. In contrast, sparsely populated regions may find it harder to justify large-scale investments in water infrastructure.

Local governance and regulatory frameworks further influence water management outcomes. States with proactive and transparent water authorities tend to perform better in both water reserve margin and NRW metrics. For instance, the Penang Water Supply Corporation (PBAPP) is lauded for its effective policies and community engagement initiatives, contributing to the state’s impressive water management record.

Understanding the variations in water reserve margin and NRW across Malaysian states is crucial for developing targeted strategies to enhance water security nationwide. By addressing the unique challenges and leveraging the strengths of each region, Malaysia can work towards a more sustainable and efficient water management system.

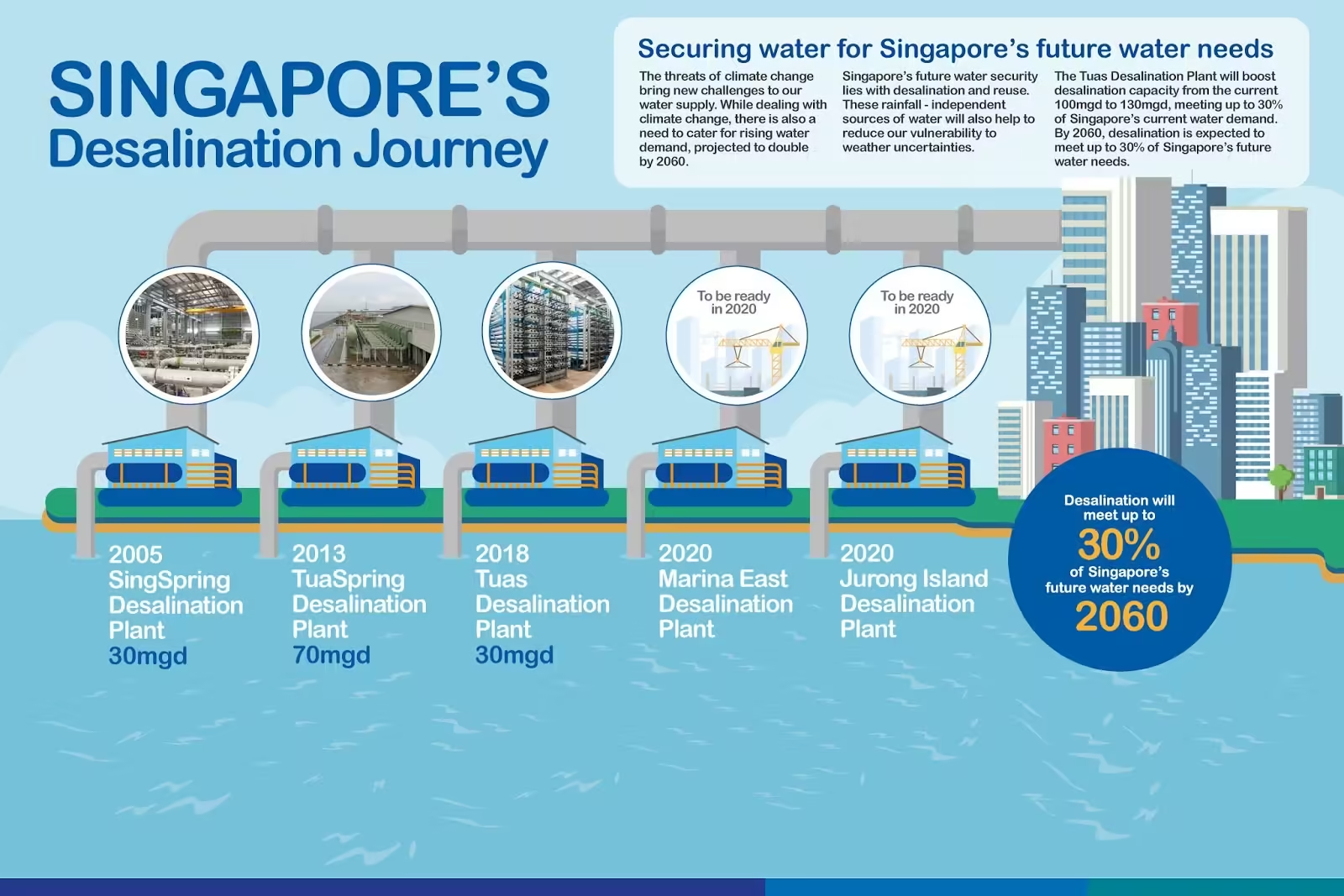

Singapore’s approach to desalination is a cornerstone of its water sustainability strategy. Utilizing reverse osmosis, the process involves pushing seawater through membranes to remove salts and minerals, producing pure drinking water. This method is energy-intensive, requiring about 3.5kWh per cubic meter of seawater treated. As part of its ‘Four National Taps’ strategy, desalination, alongside local catchment water, imported water, and NEWater, contributes significantly to the nation’s water supply. Currently, desalination plants provide up to 25% of Singapore’s total water needs, with plans to increase this contribution in the future. Image source: Singapore National Water Agency

Future Technologies for Water Management

As the global water demand continues to rise, the implementation of advanced technologies becomes essential for sustainable water management. Emerging innovations are poised to revolutionize the way we monitor, manage, and conserve water resources. Among these advancements, smart water meters, IoT-based leak detection systems, and AI-driven water management platforms stand out as pivotal solutions.

Smart water meters are instrumental in providing real-time data on water usage, enabling more accurate billing and the identification of irregular consumption patterns. These devices can significantly enhance the efficiency of water distribution systems by allowing utilities to swiftly address issues such as leaks or unauthorized usage. The integration of smart meters has already shown promising results in cities like London and Singapore, where they have contributed to a notable reduction in non-revenue water (NRW).

IoT-based leak detection systems represent another leap forward in water management technology. By deploying a network of sensors throughout the water distribution infrastructure, these systems can detect and locate leaks with remarkable precision. This proactive approach not only minimizes water loss but also reduces repair costs and downtime. One exemplary implementation is in Tokyo, where the adoption of IoT leak detection has led to a dramatic decrease in water wastage, thereby improving the city’s water reserve margin.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is also playing a transformative role in water management. AI-driven platforms can analyze vast amounts of data from various sources to predict water demand, optimize distribution, and even forecast potential failures within the network. These insights enable utilities to make data-informed decisions, enhancing both efficiency and reliability. In Barcelona, AI-powered systems have optimized water distribution, ensuring an equitable supply while conserving resources.

These technological advancements are not just theoretical; they have been successfully implemented in various parts of the world, showcasing their potential to improve water reserve margins and reduce non-revenue water. As these technologies continue to evolve, their adoption will be crucial in addressing the challenges of water management in the future, ensuring a more sustainable and resilient water supply for all.

Final Say

Throughout this blog post, we have delved into the intricate aspects of water reserve margins and non-revenue water, establishing a comprehensive understanding of these crucial components in water resource management. Maintaining an adequate water reserve margin is essential for ensuring a reliable water supply, especially in times of unexpected demand surges or supply disruptions. Equally important is addressing non-revenue water, which encompasses both physical losses due to leaks and administrative losses related to billing inefficiencies.

The analysis of international standards and Malaysian statistics reveals a pressing need for improved water management practices. The Malaysian context, in particular, underscores the significance of adopting stringent measures to reduce non-revenue water levels and enhance the resilience of water supply systems. The reduction of non-revenue water not only conserves valuable water resources but also translates into substantial cost savings and improved service delivery.

Policy recommendations grounded in international best practices can offer a roadmap for achieving these goals. Firstly, the implementation of advanced metering infrastructure (AMI) and continuous monitoring systems can greatly improve the accuracy of water usage data, facilitating timely detection and repair of leaks. Secondly, adopting a holistic approach that includes both technical solutions and community engagement is crucial. Educating the public on water conservation and involving them in reporting leaks can significantly enhance efforts to reduce non-revenue water.

Furthermore, fostering collaboration among governments, water utilities, and stakeholders is paramount. Establishing clear regulatory frameworks and incentivizing best practices can drive the adoption of innovative technologies and efficient management strategies. Regular audits and benchmarking against international standards can also help in maintaining accountability and transparency in water management efforts.

In conclusion, ensuring sustainable water resource management requires a concerted effort from all sectors of society. By focusing on reducing non-revenue water and maintaining robust water reserve margins, we can safeguard our water resources for future generations. We must embrace both technological advancements and community-driven initiatives to build resilient and efficient water supply systems.

Pingback: Nature 101: The Iconic Greenpeace's History, Events, And Famous Ships

Pingback: Nature 101: Icebergs - Nature's Frozen Deadly Giants